The Shoulder

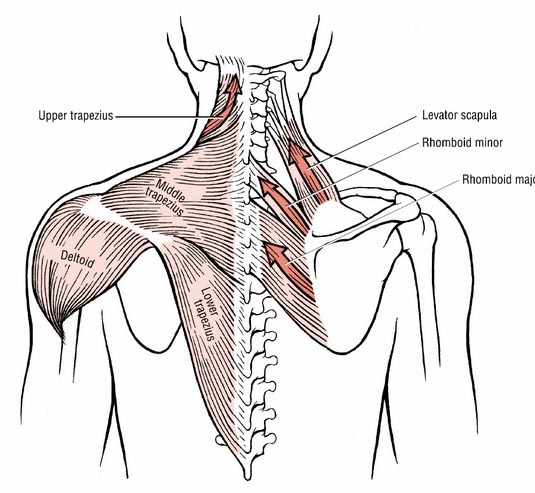

The shoulder is one of the most complex joints in the human body and as such is vulnerable to all sorts of problems and injuries. It is a relatively shallow joint in comparison to our hip joint and is extremely dependant on muscle tone for correct alignment and joint stability. Imbalance in any of the […]